Breastmilk composition and child health – Q&A with Dr Meghan Azad

Dr Meghan Azad joined us for an online Q&A. She is the co-Lead on the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) Study (Manitoba site) and also a Research Scientist at the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba (CHRIM).

Dr Meghan Azad joined us for an online Q&A. She is the co-Lead on the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) Study (Manitoba site) and also a Research Scientist at the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba (CHRIM).

Q: Meghan we’d love to hear a bit about your work – what are you working on right now?

Meghan: I work with the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) Study. We are following 3500 children from pregnancy onwards to study the developmental origins of health and chronic disease.

My role in the study, lately, has been focused on breastfeeding and breast milk composition. We have collected detailed information about feeding patterns (breastfeeding duration, exclusivity; introduction of foods; pumping; etc). We have also collected breast milk samples, and my lab is studying several components to understand how breast milk influences infant health and development.

Some of the components I am studying include:

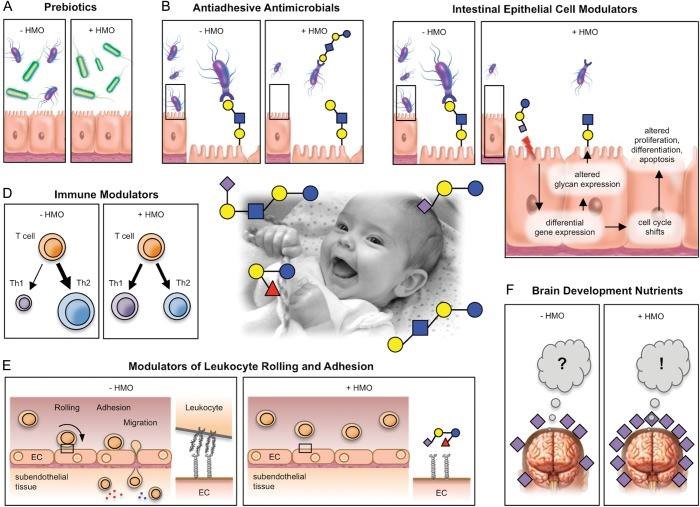

- Human milk oligosaccharides (indigestible sugars that act as prebiotics for the baby’s gut bacteria)

- Microbiota (live ‘probiotic’ bacteria in breast milk)

- As well as hormones, fatty acids, and cytokines (molecules that shape immunity)

PSG D: That’s a great list! Can you give us an idea of what you hope to find?

Meghan: We are looking for associations between milk components and infant growth, neurodevelopment, and immunity. We are measuring various outcomes related to obesity, allergies and asthma.

Q: Were any of the 3,500 children in the CHILD study breastfed past the age of 2?

Meghan: Yes, about 8%

PSG A: So, I wonder if you can work out anything about the health of those who fed till, say 3, vs those who fed to age 2?

Meghan: Sadly we did not ask again about breastfeeding after age 2! We are now seeing the kids at 8. I’m advocating to ask again so we can get the final duration for those 8%.

PSG A: OMG, yes. You should totally ask about breastfeeding duration. This is a golden opportunity!

Q: Who commissioned the CHILD study and why? Is it government funded?

Meghan: The CHILD Study is funded by the Canadian government through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Allergy, Genes and Environment Network. It was designed to explore (very broadly) the genetic and environmental factors that influence the development of allergies.

PSG B: Do you think your research could inspire other countries and governments to fund similar research?

Meghan: I hope so! I think pregnancy cohorts are so important. So many chronic diseases begin very early in life. To understand their development, we need to start early. And it is difficult to collect information retrospectively. Prospective studies are resource-intensive, but they provide critical information. There is going to be a new Canadian cohort that starts even earlier (pre-conception)

PSG A: There are other longitudinal studies. e.g. there’s one in the UK called ALSPAC, but I think they’ve not collected the same samples.

Meghan: Yes, ALSPAC is an excellent study. Another is the Generation R cohort in the Netherlands. And the RAINE study in Australia. But not all have collected breast milk samples.

Q: How do you do experiments to find out about between what’s in breastmilk and child health? Do you test breastmilk, or child health, or both?

Meghan: We do both! We have collected breast milk samples, so we can analyze specific components (eg. proteins, fats, prebiotic oligosaccharides, probiotic bacteria). Then, we follow the infants as they grow up – we have measured their immune profiles, body composition, rates of allergy, infections, etc. So we can link the milk composition data to the health outcomes.

Natural term breastfeeding and social stigma

Q: Although the WHO recommends feeding until at least 2 years, in the UK there is significant social stigma to BFing older babies and children – is it the same in Canada?

Meghan: I’d say there is some stigma. I have a couple of projects that will address this: one about Breastfeeding on Instagram, and another about breastfeeding education to school children (I think that if we teach children from a young age about breastfeeding as the normal and healthy way to feed babies, this will foster a ‘breastfeeding friendly’ society, and reduce social stigma associated with breastfeeding… it’s a long-term plan, but I think it’s worth the effort).

Actually we found a curriculum from the UK that we may use as a starting point.

We celebrated Breastfeeding Week in Canada from October 1-7. This year in Winnipeg, I helped with a campaign to normalize breastfeeding in public:

Studying the Variability of Breastmilk

Q: Given what you know about the variability of breastmilk, what variables (if any) do you think might produce changes to milk that are detectable in a snapshot study with, say 30 participants per group?

Would things like length of feed, time of day, pregnancy, hormonal birth control etc – be detectable at this size of study?

Meghan: For sure, the things you have suggested are important: time of day, time postpartum (age of infant), stage of feed (fore/hind milk; full feed).

We’ve also seen differences in various components according to: maternal ethnicity (genetics), age, body mass index, diet, smoking, and gestational age of infant (though I imagine this would be less important after 2 years).

And season (winter/summer/spring/fall). This one intrigues me.

PSG A: Wow! I wonder if the amount of time spent outside affects it too? (I’m thinking about sunlight)

Q: Just because it’s super interesting, please could you tell us more about the seasonal variations of breastmilk?

Meghan: There was a recent study on HMOs finding differences by season. This was in the Gambia, where they have wet and dry seasons associated with dramatic ‘feast or famine’ seasons where mothers gain and lose weight.

But, even in our Canadian population, I am seeing some differences by season. This really surprised me! We are still trying to understand the data… it could be related to sunlight exposure (vitamin D); or maybe seasonal infections… we are really not sure at this point, but it’s intriguing!

I found a study in cows where they show seasonal variation in milk composition, but it’s hard to translate this to human milk since all the cows (calves) are born around the same time of year. So it’s difficult to tease out season from lactation stage.

PSG E: What do you hypothesise the reason for this could be? I mean, why might children’s bodies want different things at different times of year?

Meghan: In some cases (like the Gambia) it could be more about what the mother’s body can produce, vs. what the infant needs.

PSG F: Could it be true about “rich” and “poor” or “weak” milk?

PSG F: Sometimes mums are told to top their baby up with a formula because their milk is weak…

That it doesn’t have enough nutrients. Basically that every mother’s milk is of different quality.

Meghan: Well, it is true that every mother’s milk is *different*. We see that more for some components than others. In some cases it may be possible that a particular mother’s milk is deficient in a particular component (perhaps related to her own health, or diet) – but this would need to be determined on an individual basis.

This is actually done regularly for premature babies (many NICUs have milk analyzers to check on the calorie/fat/etc. content of each mother’s milk, and the milk can then be fortified if necessary).

The Infant Microbiome

Q: What do you think is the most interesting or surprising link between what’s in breastmilk and child health?

Meghan: For me, the most interesting link is with the infant microbiome. This was my ‘entry’ into breastfeeding research – I was studying the infant microbiome (gut bacteria) and we found that breastfeeding was a very strong determinant of microbiome composition.

PSG H: I was going to ask how you got into breastmilk research, it sounds fascinating

PSG E: Funny, that was kind of my way “into” breastfeeding science too ?

Meghan: The gut microbiome plays a role in so many aspects of health (from allergic disease, to metabolism, to neurodevelopment) – and it is shaped very early on by breast milk.

Human Milk Oligosaccharides

Q: What is the most interesting thing that you have seen so far in your research?

Meghan: It’s all interesting! 🙂

But I am most fascinated lately by the Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs). These are non-digestible sugars that the baby does not digest… they were largely ignored for many decades and thought to be unimportant. But now we know that they are food for the baby’s gut microbes!

PSG G: They sound really interesting and I am hoping that we will be able to see more studies into their benefits

PSG D: Meghan we’re very interested in HMOs too. I know your research has been infant nutrition in on early life.

The World Health Organisation recommends we feed until at least 2. If you were to guess, what role do you think HMOs would play for toddlers over 2?

Meghan: Good question. In general, there is much more research on milk composition in early infancy. I have not seen much research focusing on milk composition (HMOs or otherwise) after 2 years.

In the CHILD study, we only collected one milk sample (around 3-4months) so we cannot look at longitudinal changes in milk composition in this cohort. But the changes in milk composition over lactation are one of the fascinating things about breastmilk!

PSG D: It’s amazing stuff isn’t it!

Meghan: I would guess that HMOs after the age of 2 would continue to ‘feed’ the infant/toddler’s microbiota. HMOs also have other functions beyond the microbiota – to a small degree, they are absorbed into infant circulation where they can have systemic effects. I wonder if the degree of absorption might change in older children, since the newborn gut is “leaky” but this changes over time.

PSG F: This would be interesting to know because there are many babies who were bottle or mixed fed just after and some time after birth so do they still absorb the HMOs after, say, 5 weeks of age or once they start being exclusively breastfed?

Meghan: I would think so, but I have not studied this specifically.

PSG E: Can I add that a child’s microbiome doesn’t resemble an adult’s till the child is about 3? I feel like that might be relevant here.

Meghan: Yes this is true. The microbiome changes during infancy, eventually moving towards an ‘adult’ composition. We are still learning about how/when this happens (some people say 2 years, others say 3). But clearly the diet is a main driver of this ‘microbiome evolution’.

PSG E: Oh, I so badly want to know whether this is different for breastfed children!

Is my (bf) 5yo’s microbiome more like mine, or like that of her 1yo sister?

So fascinating! So hard to test! if I ever rob a bank I’ll give you all the money to do these experiments.

Meghan: You could send your poop to get analyzed! 🙂

(and theirs).

The HMOs would always be accessible to the microbiome. But whether they are absorbed into circulation might change over time (I think they would still be absorbed somewhat – I believe this has been shown in experiments with adults – but they, and other milk components, might be absorbed to a lesser extent in older children)

PSG D: That’s not the first time poop has been mentioned in our discussions!

If we analysed poo, what would we see in it? Could it tell us something about how well the body is accessing the HMOs?

Meghan: If you had the gut microbiota analyzed in your kids (and had some comparison non-BF kids), you could see if/how they differ.

PSG D: Could it tell just anything about whether the child could access the HMOs = or simply that they passed through the body?

Meghan: For that you would need to analyze HMOs in urine/stool/blood.

PSG A: I think the idea is that the child’s body doesn’t access the HMOs. Their microbiome does.

PSG D: Meghan: Yes that’s what I meant, in the stools.

Meghan: Both. The microbiome uses the HMOs for ‘food’. But the body also uses HMOs for other purposes.

You can look up my collaborator Lars Bode’s work on this – he has some nice review papers. His lab is analyzing the HMOs in our CHILD milk.

PSG D: Brilliant, thank you 🙂

Meghan: This is an older review, but I just love the title!

Human milk oligosaccharides: every baby needs a sugar mama.

PSG D: Ha! Brilliant!

Meghan: The figure shows the various roles of HMOs

Stem Cells

Meghan: We haven’t even talked about STEM CELLS! This is one of the coolest things in breast milk, in my opinion.

PSG F: what could you tell us about stem cells please? 🙂

Meghan: Breast milk contains maternal stem cells! In mice, they have shown that these stem cells get integrated into the offspring’s tissues, and develop into functional cells (brain, liver, etc), and remain there FOR LIFE! Isn’t this incredible?

PSG A: So, breastfed babies are actually a chimera, and include some of the mother’s cells?

Meghan: Yes! (A very small number/proportion… but… I have to think, this happens for a reason)

PSG A: That’s amazing.

Meghan: I KNOW RIGHT

🙂

PSG A: So some of my grandmother’s cells are still alive in my mum’s body.

PSG F: Off topic but apparently it’s the other way round, too? A little bit from the baby gets into its mother during pregnancy and helps her fight off for example cancer?

PSG A: That’s love!

Meghan: Fetal cells do get into the mother’s tissue. Brings a whole new meaning to the term ‘baby brain’! This also relates to the baby’s “leaky gut”. If we adults “drank” a stem cell, it would simply be digested. But in babies, the stem cells appear to be ‘absorbed’ into circulation and make their way to other body sites, where they are integrated into tissues in the offspring. So fascinating.

PSG F: It is! How long do they get absorbed for though? And what about colostrum? Is that a baby superfood and what if the baby missed out on it?

Meghan: Great questions. I am not sure. Still a new area of research.

This is work done by a group in Australia. Here’s a review.

PSG G: Is this why the cells has to be modified for HAMLET cancer treatment? Because otherwise the stem cells would be excreted in adults?

I wonder how long children can absorb the stem cells for?

Meghan: This is a great question! I am not sure.

Melatonin in milk

Q: At what age does breast milk stop containing a melatonin-like hormone or substance (enzyme? I might not have the terminology correct).

Meghan: Good question… I am not sure as this is not something I have studied, sorry!

I’ve read about how melatonin in milk has a circadian rhythm (changes from morning to night) – which I love. It’s a beautiful example of how milk is ‘programmed’ to optimally support infant development.

Child health

Q: How does breastfeeding connect to child wellness? What positive/negative correlations have you found between the two so far?

Meghan: In the CHILD Study, my team has found that breastfeeding is associated with lower rates of wheezing in the first year of life. The association is “dose dependent”, meaning that longer and more exclusive breastfeeding appears to have a stronger effect.

This also means that ‘every bit counts’.

We also find that breastfeeding is associated with a reduced risk of infant obesity. This association is also dose dependent.

My role in the study, lately, has been focused on breastfeeding and breast milk composition. We have collected detailed information about feeding patterns (breastfeeding duration, exclusivity; introduction of foods; pumping; etc). We have also collected breast milk samples, and my lab is studying several components to understand how breast milk influences infant health and development. www.azadlab.ca

Q: I’ve been wondering what it means when a breastfed baby gets ill quite often does it mean their mum’s milk doesn’t have as many antibodies as other mums’ milk?

Meghan: I don’t have a great answer for this, but there are many factors that could be contributing to a baby getting ill quite often.

It’s possible this could relate to breastmilk composition, but not necessarily. Generally, evidence shows that breastfeeding is associated with a reduced risk of infections.

PSG H: How would you know if breastfeeding is reducing infection in an infant that is prone to infection? Could it be that if they weren’t breastfed they would be even more ill?

Meghan: Possibly! It’s always hard to say with a single infant.

PSG B: I have a friend whose son is always picking things up, but we both noticed he would recover quite quickly from things. Personally I’ve also noticed that my lg also seems to bounce back from things like colds far quicker than my other half and I, so I wondered if perhaps it was more that it built a stronger immunity to fight things better rather than stopping them from getting the infections in the first place…does that make sense? I’ve seriously considered drinking my own breastmilk this week after my lg recovered from an awful cold in 2 days while I’ve felt like death for the last week! ??

PSG I: It’s how they build their immune system up – if worried always go to GP. I would be surprised if a link was shown to breastmilk composition though?

Breastfeeding duration

Q: As a mother who is breastfeeding an almost 2 year old, I often face negativity in terms of continuing to breastfeed for as long as I have.

Has your research shown any benefits to long term breastfeeding? Do any of the compounds etc that you’re looking into decrease over the duration? I often hear of health professionals advising that there’s no benefit to breastmilk after 6 months and that it’s lacking in things that a child needs, is any of this true? (I would hazard a guess that it isn’t but it’s nice to have science to back my stance up!)

Meghan: Yikes! No benefit over 6 months? This is definitely not true.

My research shows a ‘dose dependent’ benefit (i.e. each additional month provides an additional benefit). We see this out to 12 months for sure; and in the future I will be looking at the period from 12-24 months.

After 6 months, the baby does start to need additional nutrition (from solid foods), but breastmilk still provides many benefits.

As well, the act of breastfeeding is beneficial for other reasons beyond nutrition.

Thanks for a fascinating talk, Dr Meghan Azad!

PSG C: Once again my mind is blown by breastmilk! I don’t think we will ever truly know the magic of it all…certainly not in this lifetime…so glad to be part of this research into it though!

PSG D: Thank you so much for coming Meghan, absolutely fascinating – you have an awesome job!

Meghan: Thanks everyone!

I do have an awesome job 🙂

I think it’s fabulous that you are all so interested in research/science/evidence. Thank you for inviting me to ‘chat’ with your group!

Links

Dr Meghan Azad’s work:

Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) Study.

Breastfeeding, maternal asthma and wheezing in the first year of life: a longitudinal birth cohort study

Gut microbiota of healthy Canadian infants: profiles by mode of delivery and infant diet at 4 months

World Breastfeeding Week: Winnipeg campaign aimed at normalizing breastfeeding in public

Other links:

AllerGen – the Allergy, Genes and Environment Network.

Breastfeeding – an educational resource for schools – Leicester Healthy Schools Programme

American Gut – one of the largest crowd-sourced, citizen science projects in America. It looks at the human microbiome and health.

The Bode Lab – dedicated to research on Human Milk Oligosaccharides

Study: Human milk oligosaccharides: every baby needs a sugar mama.

Article: Breast milk stem cells may be incorporated into baby

Study: Cells of human breast milk