Introduction to Mass Spectrometry & REIMS: a Q&A with Dr Simon Cameron

Today we’re opening our notebooks to reveal a discussion our BOBAB and UKBAPS PSG groups had with Dr Simon Cameron in September 2017 as part of designing their “what’s in breastmilk?” study.

Simon: Hello everyone, my name is Simon and I am a postdoctoral researcher at Imperial College London. I work primarily on using mass spectrometry (mainly REIMS) to better understand microorganisms that cause disease and how we can diagnose infection quickly and accurately.

We’ve started doing a lot of work on using REIMS to analyse other samples (pretty much anything we can get our hands on!) to answer interesting questions and this is how we met Natalie Shenker who introduced us to Parenting Science Gang.

How does REIMS work?

Q: Please could you tell us a bit about REIMS – I understand it’s new and hasn’t tested human milk before?

Simon: REIMS is a technique which analyses a sample by heating it up very quickly. When a sample is heated it evaporates and turns into a gas. Inside this gas are ions which are what we analyse using mass spectrometry.

Q: Do you test more than one sample at once? What treatment does the milk have before you put it in the machine? What mechanical process is there? What does the machine test?

Simon: We test 2 mL of milk sample at a time but we do it in a plate that has wells for 24 samples at a time. Each sample takes about 15 seconds to analyse. The great thing about REIMS is it doesn’t require anything to really be done to the sample before we can analyse so it’s very quick and easy to do.

Q:PSG C: Please could you tell us a bit about your study on cow’s milk? That sounded really interesting – and possibly the closest to our study so far.

Simon: We’ve used REIMS in my lab mainly to study microorganisms (such as bacteria) which cause infections. We’re developing it as a tool to be used in hospital laboratories to figure out what is causing an infection.

We’ve done some work using REIMS looking at milk from cows with mastitis. This is caused by bacteria infecting the udders of cows and is pretty unpleasant and painful for the cow and means its milk can’t be used.

At the moment, when a cow has mastitis, the farmer doesn’t have the time or the money to figure out what bacteria is causing the infection so a vet would normally treat the cow with broad-spectrum antibiotics.

These antibiotics can lead to the development of drug-resistant bugs so we used REIMS to analyse milk from cows directly to look for markers of what is causing the infection.

Instead of the usual methods which can take up to a week, we were able to do this in under 30 seconds a sample.

PSG C: Wow, that’s a significant improvement!

Simon: This means that a farmer can use much more targeted antibiotics which are better for the cow and mean that less drug-resistant bugs will develop.

PSG E: That’s amazing I wonder if the same applies to human mastitis.

PSG G: Does this mean your technique would be able to identify any microbes in the human milk? Would we expect to see any microbes in human milk (if the mum doesn’t have mastitis).

Simon: It’s an area that we are interested in looking at in more detail if we can get the samples

PSG H: Sorry slight tangent here, but am I right in thinking there are two kinds of mastitis? One being bacterial and the other something else?

Simon: Hi, I’m not really an expert in mastitis so I’m not 100% sure. I’m sure Natalie Shenker would be able to answer in a bit more detail but you’re right that mastitis isn’t only caused by bacteria

PSG I: I believe so, that’s why some needs to be treated with antibiotics and others resolve with self-help methods just to clear any blockages – generally milk isn’t tested to see if it’s actually bacterial infection causing the mastitis though!

PSG F: I’ve just read your comments… it’s interesting about mastitis. I had it myself and I carried on feeding my baby as I was told it’s safe, even though there was no proof for it. I had antibiotics, too. This would add some certainty to human mums, too.

What’s the most unusual thing REIMS has tested?

Q: More of a light-hearted question. What is the most unusual/strange thing you’ve tested in your machine? And what are the most surprising or unexpected things you’ve discovered so far?

Simon: Hi, I’m not sure what the most unusual thing is we’ve analysed. I’ll list some and maybe you can decide what you think is the most unusual: bacteria, faeces from cows, rats, humans, and babies, meat samples (pork, turkey, beef, chicken), plant leaves, urine, cooking oil, blood, and algae. There might be more but I can’t think of them now.

PSG L: I like it! It looks almost like to went, “Hmm, now what? Oh, here’s my lunch, I’ll test that. And a leaf from the bottom of my shoe …”

Simon: That’s pretty close to the truth actually. As the instrument is fairly cheap to run, it doesn’t cost us anything to try something new out.

Variation of breastmilk

Q: We know breast milk is very variable. We also know that the numbers in our study won’t be enough to tease out variations due to factors that show subtle differences. But Simon I also know that your software compares and analyses samples.

Are you able to give us any advice on how can we get an idea of what is, and isn’t worth comparing?

Can we make sensible comparisons on your machine given the numbers involved?

PSG C: Or to put this another way – we have about a zillion variables we’d like to test. How do we work out which are reasonable (if any!) to ask you to compare?

Simon: It’s always difficult to know how many samples you would need. If we could have 20/30 per group to compare to one another that would be fantastic but I think anything above 10 per group would give us enough of an idea to see what could be interesting to look at in a larger study.

PSG C: In general, in experiment design – how many variables is sensible to look at in an experiment like ours? (I’m aware I’m probably asking how long is a piece of string!)

Simon: It’s not really a question of how many variables in my opinion, but how many samples you have for each variable. It’s better to have three groups of ten samples than ten groups of three samples but ok to have ten groups of ten samples if that makes sense.

PSG C: Yes I think so. Ratio of samples to variables. The more it’s weighted to samples, the better. Is that about right?

Simon: Yep, I would say so

PSG F: Differences between morning/ evening/ night time milk, healthy mum or mum with a cold, healthy child or child with cold… these might be interesting? I have read something about these topics but not sure if the information was from some valid scientific studies.

What can REIMS find in milk?

Q: Have I understood correctly that you find out how many macronutrients are present? What else can you find out?

Simon: In terms of what we can look at using REIMS, we normally see things like fats and lipids and other small molecules that we call metabolites We can’t see proteins using REIMS but the really exciting thing about this study is we’ve never analysed breast milk before so I’m sure there’s a lot of interesting things that we haven’t seen in other samples before.

PSG F: Yes, there seems to be a lot of guessing about human breastmilk.

Simon: That’s the best thing about my job, as we will definitely be the first people in the world to do this experiment!

PSG C: This sounds very exciting! Might find things in human milk that no one knew were there?

Simon: There’s a lot of things that you can see with mass spectrometry that you can’t study with other techniques that may have been used before

Q: Will we be able to see antibodies in the BM?

Simon: You could, using other mass spec techniques but not really using REIMS as they are a bit too big for our approach

PSG E: Aww 🙁 will it show us any immune type results or only nutrition ones (pardon all my technical terms lol)

PSG C: That was a good question! Let’s put that one on the email list – but from Sophia and Amy’s meeting with Natalie, we reckon the machine might be able to see HMOs

PSG E: At the risk of showing I haven’t done my homework, what are HMOs?

PSG C: HMOs are particularly interesting because you can only get the in BM I have just the thing! One sec … https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Ug1Jge29yybh7CEqpuLl8PWsMZ35O244JJ4rpvADwwA/edit?usp=sharing

PSG E: Sounds so interesting!

How can we know what molecules REIMS will detect?

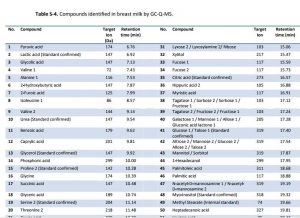

Q: We’ve looked at some papers about using mass spectroscopy to work out what is in breast milk, and although we haven’t always understood all the details(!), some of them have given us useful lists of the constituents (compounds? molecules?). Some of them helpfully give us their masses as well.

Is it the case that REIMS will be able to detect any of the constituents on lists such as these (see image) as long as their masses are in the detectable range of REIMS?

PSG D: Just realised that that image is almost impossible to read! It’s a table with the compound name e.g. Glycolic Acid, the target ion (Da) (I am assuming that this is the mass in Da), and the retention time (which I am guessing that we don’t need). Simon: Looking at the list I think we will be able to see quite a lot of them, particularly the acid ones. What determines whether we can see them or not?

Simon: It’s mainly the chemical structure of the compound which depends whether or not it will form an ion when we heat it using REIMS. Somethings become an ion very easily whilst others can be a bit more stubborn.

PSG D: Oh okay – so the list of compounds that REIMS produces, doesn’t necessarily tell us all the compounds that are within a particular mass range. There may be others that just don’t ionise easily. So rather than our results telling us what’s in breast milk, will they be better for telling us which compounds change in concentration in different child ages?

Simon: Mass spectrometry is quite annoying as a field because there isn’t one technique that tells you everything. Each technique will look at a different snap shot of a sample.

PSG D: I’m still pondering the nature of the snapshot! If we analyse the same sample more than once, how likely is it that we’d get the same results? Is there a good chance that some of those stubborn molecules would ionise the second time, or would they be in such small numbers that they’d be ignored by the analysis software as noise?

Collection of BM

Q: Does the milk need to be collected in a sterile way? Does it/can it be expressed directly into the test tube?

Simon: I think if we are going to analyse the sample quite quickly after they are expressed, then I don’t think we need to worry about them being too sterile, particularly if we can keep them cold in a fridge or cooler bag.

Simon: We can provide lots of tubes that can hold up to 50 mL of milk – I think I have about 500 in our lab at the moment which we only use slowly.

PSG E: 50 mls those were the days. What is the smallest sample size you could use?

Simon: Ideally 2 mL would be the smallest we could easily deal with.

Results

Q: Would we be able to see any results? If so, how soon and where?

Simon: Definitely, we will be able to do a lot of the data analysis and maybe we can arrange a day where we meet up and discuss the findings?

Validation

Q: How important is validation? We were originally planning to validate at least some of the sample using another Mass Spec machine at Imperial. But Simon as you may have heard the “owner” of that machine has got a grant to do some other work and can’t fit us in now. What difference would it make to our experiment if we didn’t validate? Why exactly do we want to validate? What does it mean?

Simon: With mass spectrometry, we can’t see everything using just one technique like REIMS. The mass spec that was proposed is different to ours so would have been able to look at other compounds, like proteins (maybe, I’m not 100% sure what system they use).

PSG A: Could you please elaborate on the type of machine needed and for which elements it would test please?

Simon: REIMS can only give you an idea of what molecules are either increasing or decreasing in relation to one another, and not give an absolute quantity of how much is present. Validating the findings on another machine might allow you to do this and would give the findings a lot more weight.

PSG C: Ah, OK, so it’s good to have. If we don’t manage to find another machine in time, what would that mean in practical terms? Would it still be a good piece of research in its “invalidated” state?

Simon: I certainly don’t think it’s the end of the world. We can always keep samples in our -80C freezer to do more analysis on at a later date.

PSG C: Ah, so if we don’t find another mass spec machine in time, there’s a possibility of a follow up?

Simon: I think so and it would give us time to figure out what the really interesting samples are that we might want to look at in more detail.

PSG E: So, can the samples be reused once they have been through your machine? Simon: yep, we only analyse a small amount so there is still more than enough to use in other experiments.

PSG A: Am I right in thinking a tof machine would show more (I’ve no idea about anything scientific)?

Simon: We use a ToF instrument to analyse the ions that we generate using REIMS. The difference between other types of mass spec is how the ions are generated.

Freezing

Q: Would freezing the samples add in another level of certainty, or is testing previously frozen samples a generally done thing in the world of mass spectrometry?

PSG B: I believe that it’s been shown that freezing breastmilk destroys some of its immunological properties. We would need to take that into account.

Simon: It’s always a problem freezing the samples, but as long as you do the same thing to all of your samples you shouldn’t introduce a lot of bias into the experiment. Our freezer stores them at very cold temperatures which is quite normal for mass spectrometry experiments.

The main thing we’ve found is that you shouldn’t freeze and thaw the samples too many times.

Number of participants in sample groups

Q: Hi Simon, thanks for answering my question the other day about how the software will compute statistical significance. Is there a guideline to how many samples we would need per age group to give robust results? (In my field of economics we talk about >30). Thanks.

Simon: Hi, it’s always a difficult thing to figure out. As a rule, the bigger the difference between the different types of samples the fewer number of each sample we will need to see it. We can use this study to work out what we call statistical power, which is how many samples we would need in a larger study to have really robust results.

For the first study, I think your figure of 30 would be a sensible one to aim for.

PSG M: Is 30 per age group a possibility? We may need a bigger seminar room…

PSG C: In what sense are you asking? Do you mean can we get enough people? As we don’t need to limit recruitment to the group and BOBAB and UKBAPS have about 30,000 members between them, I think we’ll be good for people. Or are you asking about something else like logistics at the hospital?

PSG M: I think I read about a room being arranged for 50 or so people. Or can we send in samples by post?

PSG C: We can stagger people coming all day. If we go for a truly MASSIVE number of people I wonder if it makes sense to have some other larger venue nearby for us to congregate. If we send samples by post it’ll cost us £££ for courier fees.

PSG M: So if we aimed for 30 in each age group e.g. <6m, >6m, 1+, 2+, 3+,4+,5+ that’s 210 women which sounds do able.

PSG C: Plus possible tandem feeders and one siders.

PSG M: I project manage research projects alongside my research work 😉

PSG C: very pleased to have you here! 🙂

PSG M: Happy to be here, it’s a lovely combination of my work life and interest in breastfeeding 🙂

Study design

Q: I’d like to know about the sample collection, are there any rules? E.g. age of the baby, storage…

Simon: I’m not too sure what the study design is in terms of the age of the baby but I think our plan is to try and analyse the samples on the same day that they are donated.

We can easily analyse 500 samples in a day so we won’t really need to worry about long-term storage.

Q: Regarding fat, there seems to be a lot of opinions about “rich and poor” milk as well as milk from mums 1 week / 3 months / 6 months postpartum being of different quality. Would you be keeping a record about postpartum period?

PSG C: The design of the experiment is up to us as a group. That kind of thing is up to us to decide. Come join us in the main group to get involved! However – this experiment is specifically to look at milk from older children. So although we may include milk from younger children it will be there for comparison.

PSG F: It’s great news about milk for older children. Most info seems to be about milk for under 6 months of age.

Q: What are you testing for and how will the results be worked out? will you have to compare the age of the infant and what time of day its collect or is just a case see how the milk ranges from different people?

Simon: Hi, we will be testing for things like fatty acids, other fats and lipids, and what are known as metabolites. We can perform statistical analysis on the data to see if there are differences between age of infants and time of day etc. Simon: Basically, whatever you are all interested in looking at, we should be able to see if REIMS can detect a difference.

PSG K: Thanks 🙂

PSG J: Do you expect to see differences in age of mothers?

Simon: That’s a very interesting question, and the honest truth is I have no idea. If we can get the samples though, I’m sure we would be able to see.